“A recent study published by Civil Liberties Australia has estimated that 6% of all people held in Australian prisons for major crimes (eg. murder, rape, and serious assault) have been wrongfully convicted.”

On 6 June 2022, Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk announced an independent Commission of Inquiry into Forensic DNA Testing in Queensland. The Commission’s final report, which was handed down on 13 December 2022 sent shockwaves throughout the legal community.

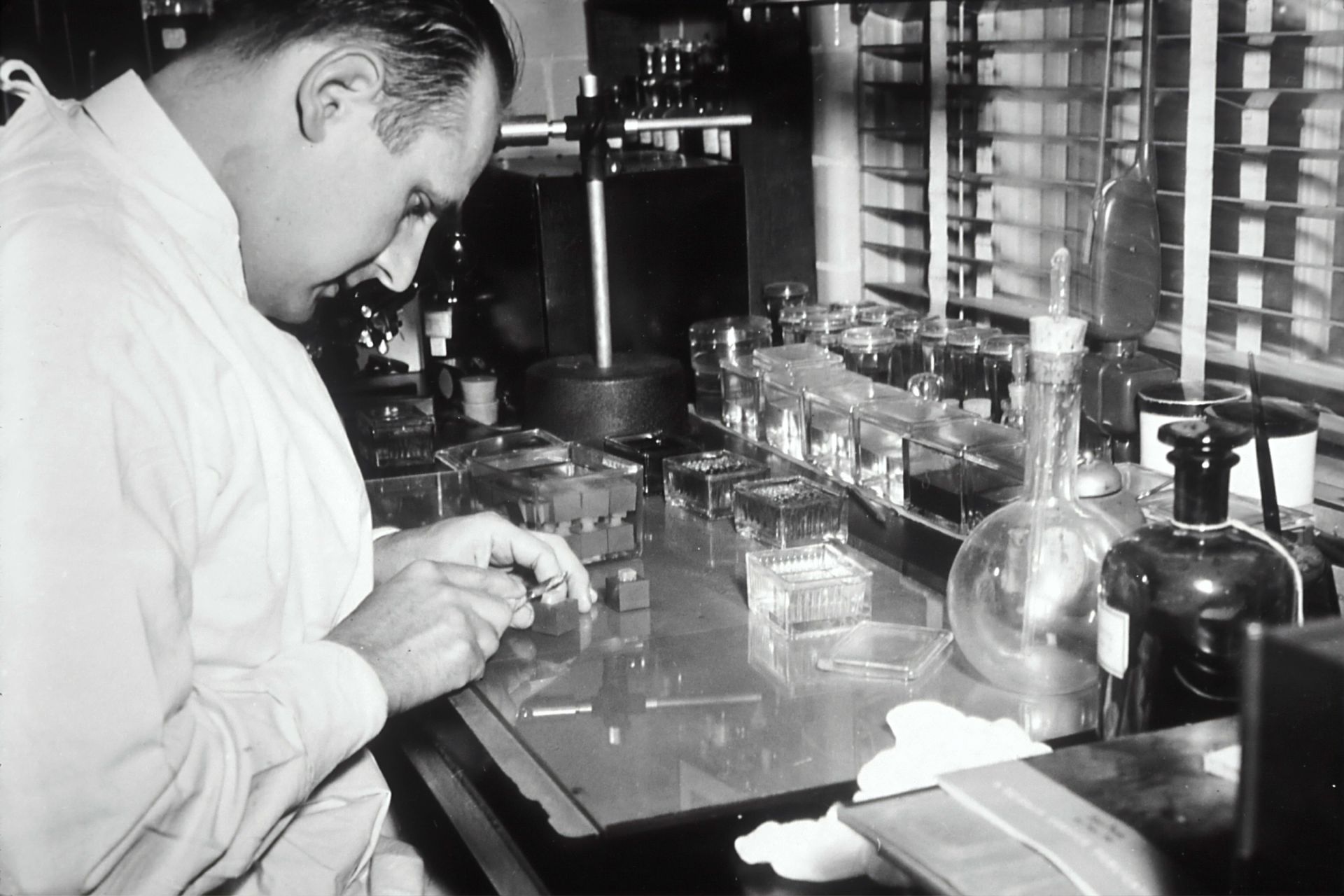

The head of the Inquiry, retired judge and former President of the Court of Appeal, Walter Sofronoff KC, called its findings a “horrible read,” referencing their revelation and documentation of “disturbing oversights” by State-run forensic laboratories in conducting forensic DNA testing over a period of many years. The reliability of the reported results of such testing was found by the inquiry to be so hopelessly wanting that the prosecuting authorities were forced to order that the DNA evidence prepared and used for thousands of previous criminal prosecutions must be reviewed and retested immediately.

In May this year, almost a year after the establishment of the Commission of Inquiry, Deputy Chief Magistrate Anthony Gett finally gave us some idea of just what the resulting backlog entails. In criminal proceedings before a Brisbane court, His Honour announced that over 10,000 prosecution cases were currently effectively on hold, awaiting re-testing of the DNA evidence.

For many years now, DNA has been often perceived as a ‘silver bullet’ when it comes to the prosecution of major crime. But now, as public faith in the State’s forensic testing capabilities wavers, we are collectively faced with the prospect that our justice system’s greatest weapon may not as be effective, or even accurate, as we had once thought. Of course, the potential ramifications are unthinkable.

A recent study published by Civil Liberties Australia has estimated that 6% of all people held in Australian prisons for major crimes (eg. murder, rape, and serious assault) have been wrongfully convicted. While that may seem to some like a small percentage of the overall prison population, the implications at a personal as well as societal level of even one such failure of our criminal justice system are of course immense. The statistic is perhaps even more concerning given that Australia is the only democratic country to have failed to ratify the United Nations provision for the availability of formal legal remedies to the wrongly convicted. While an appeal against a decision upon the grounds of a mistake of law or fact is the right of every convicted person, Australia does not currently allow the possibility of second or further appeal in cases where new evidence later emerges, whether such evidence is DNA-based or otherwise.

The very recent release of Kathleen Folbigg highlights that concern. Ms Folbigg was convicted in 2003 for the murder of her four infant children. She went through a trial, an appeal, a subsequent judicial inquiry, a review of the findings of that inquiry, and a second judicial inquiry, before it was established – 20 years after the fact – that there was reasonable doubt about her guilt, which should have led to her acquittal. She was ultimately released pursuant to a pardon granted by the “Royal Prerogative of Mercy”, a remedy exercised by government only in rare and very limited circumstances. It is as yet undecided whether her conviction will be quashed and, if so, what compensation she may be awarded.

We don’t know how far reaching the consequences of the findings reported by the Commission of Inquiry into Forensic DNA Testing in Queensland will be. So far, we don’t even have a definitive answer as to when we can expect to catch up with the backlog in cases on hold in the system. But certainly, at least, the old adage applies – Justice delayed is justice denied. What other ramifications will flow from the final re-testing, when it finally happens, is yet to be fully assessed. Perhaps the abiding question will be whether DNA evidence will ever regain the ‘silver bullet’ status it once enjoyed in the Queensland criminal justice process, and whether Queensland juries will ever so confidently trust it again?