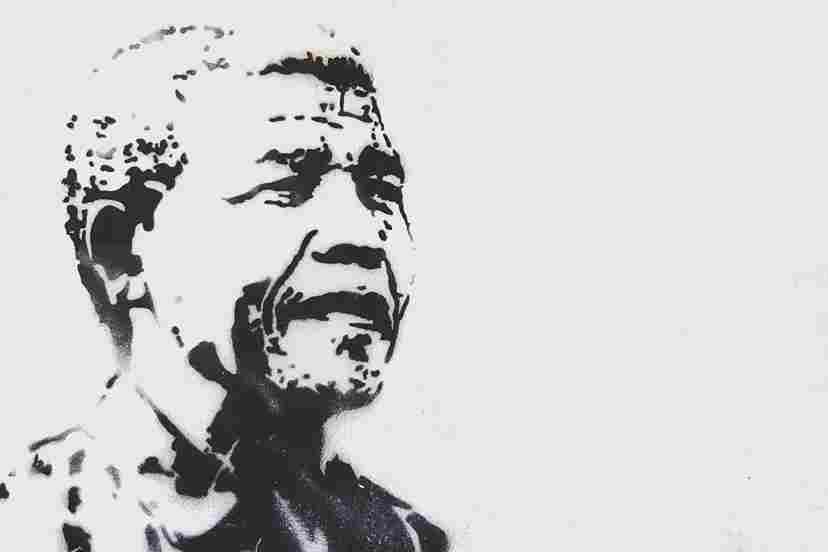

The late great Nelson Mandela served 27 years in prison for his opposition to the apartheid system of racial segregation in South Africa. When he was finally released from custody in 1990, he famously said “To deny a person their human rights is to challenge their very humanity.”

Photo by John-Paul Henry, Unsplash

Such sentiments are sometimes cynically discounted as high-minded theory, propounded by idealistic left-leaning lawyers and civil libertarians. But in truth, the practical recognition of the human rights of all citizens is essential to any truly open democratic society.

Mandela was a lawyer, but he was far from an idealistic theorist. Following his release from prison he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize and internationally recognised as an icon of democracy and social justice. When he spoke of human rights and humanity, he did so with unquestioned experience and authority.

Earlier this month, the Queensland government introduced into State Parliament the Human Rights Bill 2018, in express recognition of a series of core principles which are largely reflective of Mandela’s sentiment, including “the equal and inalienable human rights of all human beings”, and the fact that “human rights are essential in a democratic and inclusive society that respects the law.” If the bill is passed as expected early next year, Queensland will join Victoria and the ACT as the only states to have legislative protection of human rights.

The proposed legislation will be debated, and no doubt reasonable minds will differ regarding much of its detail, but there is unlikely to be any serious question about its laudable intent. Amongst other things, it expressly acknowledges basic human rights such as equality before the law, freedom of movement, expression and association, the right to a fair hearing, liberty and security of person, and freedom of thought, conscience and religion. In a democratic society we mostly take such rights largely for granted, but this move aims to enshrine them in legislation.

The act as proposed would provide that when enacting any law, the Queensland government would be required to consider whether it is consistent with human rights principles. Existing laws would likewise be checked to ensure they comply with such principles. Government agencies would be required to have regard to the human rights of the people they deal with, particularly when making important decisions affecting their lives, and courts would be obliged to consider the human rights of individuals when making decisions on legal issues that affect them.

The Attorney-General Yvette D’Ath has anticipated the real practical benefit of the proposed legislation to be in the day-to-day interaction between individual and state. “The Bill will require departments, agencies and public entities to make decisions and act in a way that is consistent with human rights,” she said. “It will require the courts to interpret legislation in a way that is compatible with human rights, along with requiring the Parliament, including Parliamentary Committees, to consider whether bills are compatible with human rights.”

If all that is correct, it’s undoubtedly fair to assume that, while the fallout may not provoke grandiose headlines, it will potentially effect positive change to the lives of many Queenslanders for a long time to come. That makes it, if nothing else, a very good start.