Lawyers are well acquainted with the Reasonable Man. After all, he’s each and every one of us, although in truth none of us at all. He’s everyone and no one, the theoretical mean of human mores, the universal yardstick of all that’s fair and reasonable.

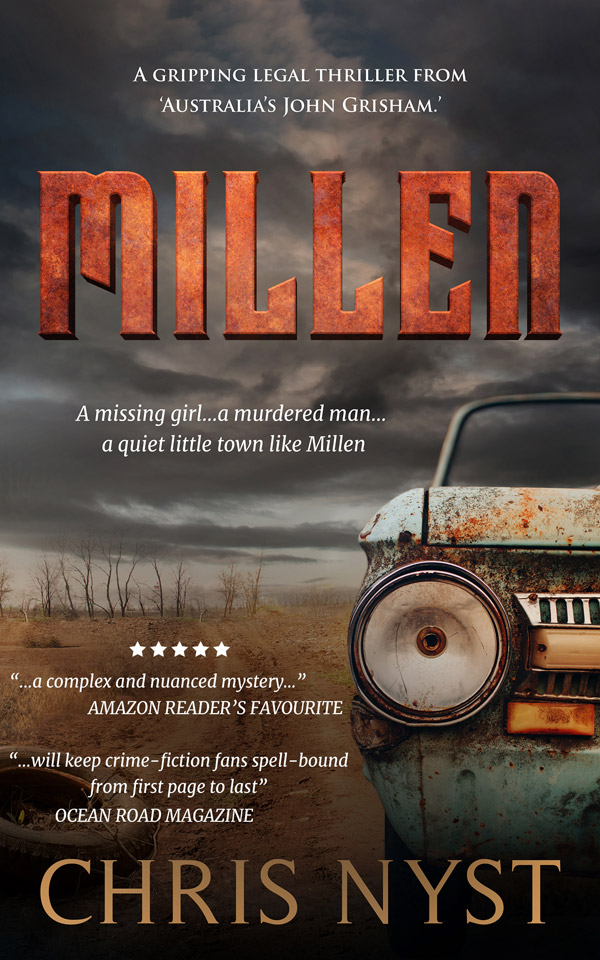

Photo: Ben White

Source: Unsplash

In British law no man is expected to be better than all men, but each must reach the standard of the Reasonable Man. Could such behaviour be expected of the reasonable man? Would the reasonable man find this language offensive, that publication obscene, or that behaviour indecent, or would he consider it acceptable and quite appropriate?

Like Reasonable Doubt the Reasonable Man cannot be defined. He’s just the notional inner moral compass in us all. One great English jurist simply described him as is “the man on the Clapham omnibus,” the hypothetical ordinary, reasonably educated and intelligent but nondescript person, against whom all other persons can be measured.

When all the carefully-worded, closely-defined legislative rules, regulations and protocols fail us, we fall back on the unerring ethical barometer of our faithful friend the Reasonable Man.

In Walter Hill’s 1996 violent Prohibition-era western Last Man Standing, aimless drifter John Smith (Bruce Willis) sets the scene for coming carnage when he sanguinely observes “It don’t matter how low you sink, in the end there’s always right and wrong.” In the Wild West it was an inspired statement of profound enlightenment, a core truth to motivate and validate what might otherwise have been considered the hero’s somewhat shabby behaviour in single-handedly annihilating several dozen human beings in cheap suits and fedoras. But, as any well-bred Englishman could easily have informed said hero, with moderately slender rumination, he was really just calling on the standards of the even-tempered, right-thinking Reasonable Man. The equation, as always, was relatively elementary. If it was fair and reasonable by all the standards of the Reasonable Man, as in this case it most certainly was, to tommy-gun a score or so vicious, pinstriped bootlegging mobsters, then it was indeed fair and reasonable, and that was that. If the man on the Clapham omnibus would have done it, then Bruce Willis was absolutely entitled to do likewise.

It is perhaps unsurprising that the great Irish playwright, critic and polemicist George Bernard Shaw, had his own contrary take on our Reasonable Man. “The Reasonable Man,” observed Shaw, “adapts himself to the world: the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore,” concluded Shaw, “All progress depends on the unreasonable man.”

I recently had the edifying experience of sharing a train journey through Northern India with another Irishman, not a writer or poet like the venerated Mr Shaw, but a humble medico with a passionate message to sell about what he perceived to be a shameless campaign of misinformation being pedalled by the western world’s pharmaceutical industry juggernauts. According to the good doctor, the giant drug companies are pouring boundless funds into propping up junk science that encourages mainstream medicine to expand their market reach into an ill-informed and unsuspecting public.

His question of me was simple: could an individual victim of such information bring civil legal action to stop it happening? The answer of course was complex, partly because, at one level at least, it involved our dear old friend the Reasonable Man. In celebrated and highly-successful civil suits like the now infamous tobacco industry and mesothelioma law-suits of the past several decades, the core question wasn’t just about the science, it included a consideration of what, at all material times, the properly-informed Reasonable Man perceived the science to be.

And that of course is where the wisdom of the great Bernard Shaw comes into crystal-sharp focus. Because while reasonable men look back in time at what their faithful friend the Reasonable Man would have thought and done when big business was indiscriminately promoting nicotine to the masses and showering workers in asbestos, it is the often more-destructive, some would say courageous Unreasonable Man, who every now and then will rock the boat. And sometimes, quite unreasonably, bring about lasting and powerful change for good.

This article was published in the Gold Coast Magazine, October/November 2016